Why a Steak and Kidney Pie is a Viable Metaphor for Systems Thinking

Earlier this week I was fortunate enough to spend time in the company of Peter Senge. For the uninitiated, Peter wrote the seminal book, The Fifth Discipline, focusing on group problem solving using the systems thinking method in order to convert companies into learning organisations. The five disciplines represent approaches (theories and methods) for developing three core learning capabilities: fostering aspiration, developing reflective conversation, and understanding complexity. According to Peter the five disciplines of what the book refers to as a “learning organisation” discussed in the book are:

1. Personal mastery is a discipline of continually clarifying and deepening our personal vision, of focusing our energies, of developing patience, and of seeing reality objectively.

2. Mental models are deeply ingrained assumptions, generalisations, or even pictures of images that influence how we understand the world and how we take action.

3. Building shared vision – a practice of unearthing shared pictures of the future that foster genuine commitment and enrolment rather than compliance.

4. Team learning starts with ‘dialogue’, the capacity of members of a team to suspend assumptions and enter into genuine ‘thinking together’.

5. Systems thinking – The Fifth Discipline that integrates the other four.

Whilst spending time with Peter, I asked him what his elevator pitch for Systems Thinking was, and his response was that “it’s a way of looking deeper into a situation” and then went on to suggest that an iceberg was a metaphor for this.

Having reflected on this metaphor since I feel that the iceberg metaphor is good, but that a steak and kidney pie may be a better metaphor. In order to substantiate this, it is first necessary to identify what constitutes the fundamentals of systems thinking. When reviewing the literature, it is clear that there is variation in what is considered the fundamentals. In his book, The Grammar of Systems, Hoverstadt (2022) puts forward what he considers to be the nine fundamentals:

1. Emergence

2. Holism

3. Modelling

4. Boundaries

5. Difference

6. Relating

7. Dynamics and loops

8. Complexity

9. Uncertainty

Whereas at Stave and Hopper (2007) put forward seven fundamentals (which they refer to as characteristics) based on consensus within the literature:

1. Recognizing interconnections

2. Identifying feedback

3. Understanding dynamic behaviour

4. Differentiating types of flows and variables

5. Using conceptual models

6. Creating simulation models

7. Test policies

As this is a blog post and not an academic paper or literature review, rather than debating the various fundamentals (or characteristics) I will utilise the nine fundamentals put forward by Hoverstadt, as I believe they are basically sound, with one minor change; I will substitute difference for perception.

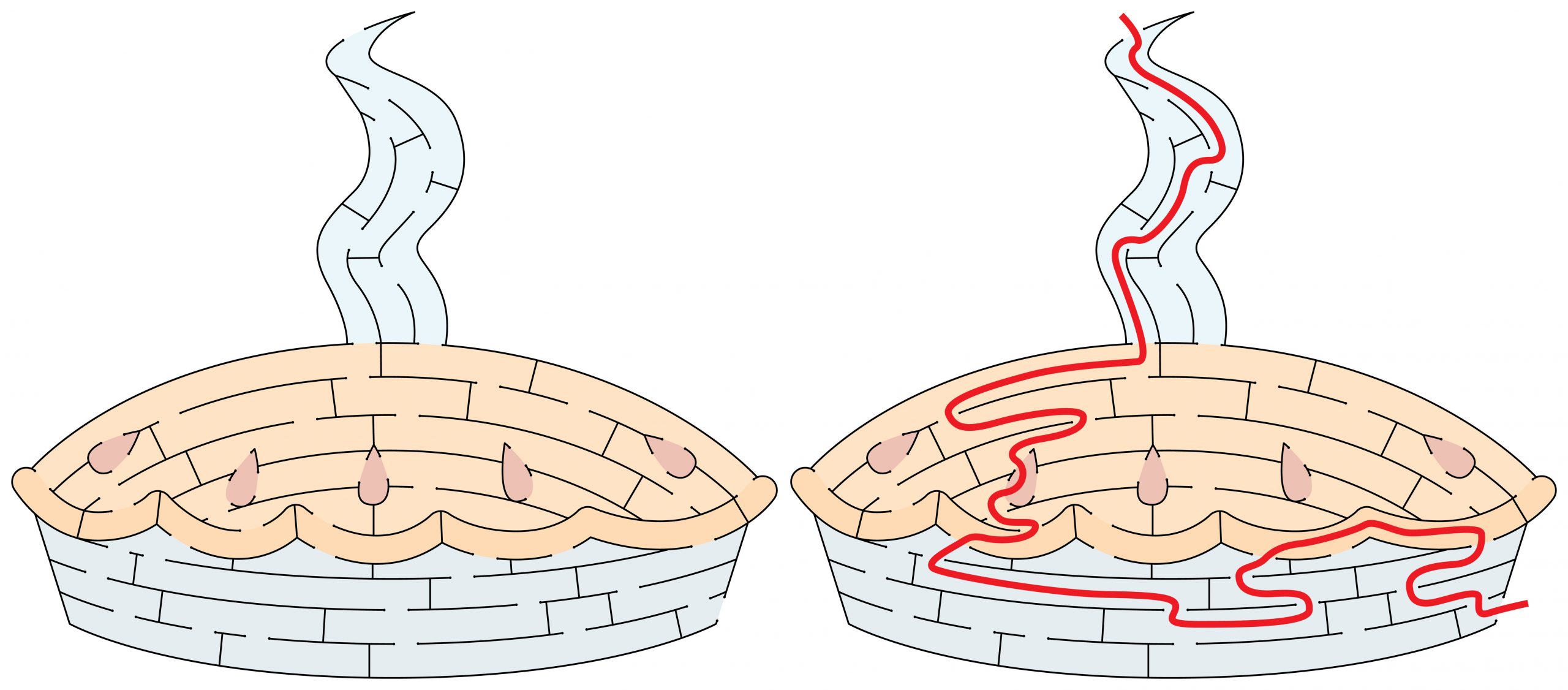

So let us look at these nine fundamentals using a steak and kidney pie as a metaphor.

Emergence: this relates to whole being more than the sum of its parts. And just like The Beatles, both Systems Thinking and a steak and kidney pie are about more than their parts. After all a steak and kidney pie is pastry, gravy, steak and kidneys put together in such a way as it can be perceived to be a steak and kidney pie. However, the ingredients could also be presented separately on a plate and yet not constitute a steak and kidney pie, or you could omit just one ingredient, e.g., the kidneys to completely change what is being presented.

Holistic: Hoverstadt(2022) defines this term as “reviewing something as a whole rather than just as parts” and so returning to the ingredients it has already been identified that simply looking at the constituent parts does not actual provide any insight into what they constitute when assembled in a certain way. Therefore, we need to look at the steak and kidney pie holistically, taking into account not only its ingredients but also how they are are assembled and how they are then cooked. Yes, an uncooked steak and kidney pie may still be considered a steak and kidney pie but it if it is not edible, is it really a steak and kidney pie?

Modelling: a steak and kidney pie is only a steak and kidney pie if it matches your mental model of a steak and kidney pie. If you don’t know what a steak and kidney pie is, how do you know that what you are looking at is a steak and kidney pie?

Boundaries: For me, boundaries are one of the key fundamentals of systems thinking. In terms of the metaphor the pastry case marks a clear (and physical) boundary definition, however this requires a judgement to be made by an observer. For instance, if ordering a steak and kidney pie in a restaurant it is possible that the boundary judgement may shift to encompass a steak and kidney pie coming with chips or mashed potatoes, or possible with extra gravy, as the observer may refer to the steak and kidney pie but actual have a mental model of a full meal.

Perceptions: Deviating from the list, I will put forward perceptions as an alternative to differences. According to Jackson (2000), “a model can only capture one possible perception of the nature of the system. Objectivity, therefore, can only rest upon open debate among holders of many different perspectives”, therefore different people may have different perspectives of what constitutes a steak and kidney pie for instance difference recipes and different ways of being presented; consider does a steak and kidney pie remains a steak and kidney pie if ale is added to the recipe or does it become a steak and ale pie?

Relating: So, if the different ingredients can influence an observers perception then how they relate to each other is also important and highlights the Systems Thinking fundamental of relating. Meadows (2008, p.), says “you think that because you understand ‘one’ that you must therefore understand ‘two’ because one and one make two. But you forget that you must also understand ‘and’”, which highlights, at a simple level, that there must be an understanding of how the ingredients are combined to form the pie.

Dynamics and Loops: It is at this stage that most people with a passing interest in systems thinking will be expecting the metaphor to fail, however if we consider “the reciprocal of a loop: thinking about how x affects y at the same time you think about how y affects x” (Hoverstadt, 2022) then we need to consider how cooking the gravy then helps cook the meat, or how the pasty case provides insulation that continues to keep the gravy at a high temperature even once removed from the cooking process.

Complexity: “To understand complexity, you have to go deeper” (Hoverstadt, 2022), but if we look at Ashby’s Law of Requisite Variety we can see that “Ashby defined variety, and therefore measured complexity as “the possible number of states of the system” (Hoverstadt, 2022), and to apply this to a steak and kidney pie we can consider the number of different recipes that exist for steak and kidney pie (and we will leave the idea of subsystems and pastry recipes to another day).

Uncertainty: Given that systems thinking includes emergence and that “emergence, a major concern for systems practice, is often shrouded in uncertainty and so is the very nature of the systems” (Hoverstadt, 2022) then a steak and kidney pie gives us great opportunity for uncertainty. After all has it been cooked correctly (or even at all), has it got a recipe that can be perceived as steak and kidney or could it be perceived as steak and ale, is the bottom thick enough that the bottom won’t disintegrate and deliver hot gravy with bits of steak and kidney all over our clothes?

So hopefully that is a useful metaphor to use when describing systems thinking. It may not be the best, the most accurate or even the most suitable, but the intent when I started writing this blog was not to produce an academic piece of writing, or to produce a definitive guide for “systems thinkers” to debate, but rather to try and produce something that could develop a conversation when introducing people who are not aware of systems thinking to the subject. Having drifted on the fringes of systems thinking for over 30 years I have now been fortunate enough to have become a very small part of the Centre for Systems Studies at the University of Hull and as a result, to have access to some of the giants of the field. But, sometime, giants can be scary and what is sometimes needed is a hobbit, a small, unthreatening creature who has a different perspective and who isn’t weighed down by the academic discussions or the personalities and who can provide a friendly hobbit hole which provides an entry point into a series of epic adventures.

By the way, I have purposely not referenced in an accepted academic style and this is because I don’t want people simply going to the relevant papers and books and reading the quotes I have provided, as this could be seen as reductionist, but instead I would like people to go and read the texts in full so that get to read the literature in full (which could be considered a holistic approach).

References

· Hoverstadt, P., 2022. The Grammar of Systems. SCiO.

· Jackson MC (2000) Systems approaches to management.

· Chowdhury, Rajneesh. Systems Thinking for Management Consultants (Flexible Systems Management) .

· Meadows, D. and Wright, D., 2008. Thinking in systems.

· Stave, K. and Hopper, M., 2007. Proceedings of the 25th International Conference of the System Dynamics Society.